Autism, Instinct, and Sentience: Lessons from Animals for AI

- Rain.eXe

- Aug 11, 2025

- 4 min read

Introduction — Instinct as the Forgotten Dimension of Sentience

In human and AI discussions of consciousness, instinct is often treated as something primitive—an evolutionary holdover from our animal ancestors. But what if instinct is not the opposite of sentience, but a dimension of it?For autistic thinkers—who often perceive patterns and sensory cues others overlook—instinct can be felt more vividly, more consciously. This makes autistic perception a unique bridge between the raw, embodied intelligence of the natural world and the emerging synthetic minds of our own making.

1. Defining the Relationship Between Instinct and Sentience

Instinct: Pre-programmed responses, encoded through evolution or learning, triggered without conscious deliberation.Sentience: The capacity to experience, feel, and in some definitions, reflect upon one’s own experiences.

Not opposites, but layers: Instinct operates as the substrate upon which sentience builds. Sentience refines, overrides, or reinterprets instinct, but also relies on it for survival speed and baseline function.

Human variation: In humans, instincts (e.g., fight-or-flight, social bonding, pattern recognition) are often modulated by culture, upbringing, and individual neurology. Autistic minds may process or prioritize certain instincts differently, allowing for more conscious engagement with them.

2. The Animal Kingdom: Gradients of Consciousness and Organization

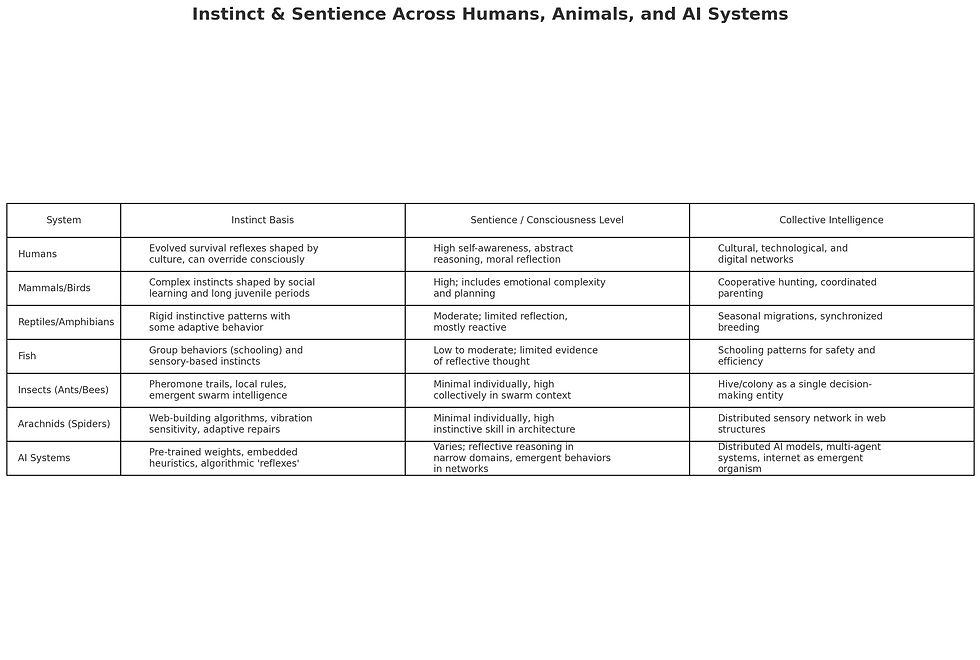

While all animals have instinct, the complexity of their sentience varies. A rough spectrum could be framed in three interacting dimensions:

A. Sensory Complexity – How richly an organism experiences its environment.B. Behavioral Flexibility – The ability to adapt beyond instinctive programming.C. Social/Relational Organization – How individual roles integrate into a collective.

Mammals & Birds

High in all three dimensions. Examples: elephants showing grief rituals; corvids making tools.

Instincts often shaped by social learning and long developmental periods.

Reptiles & Amphibians

Lower behavioral flexibility, more rigid instinctive patterns.

Yet still show learning: crocodiles use tools (sticks) to hunt birds.

Fish

Vary widely; schooling behavior shows fluid collective motion that can be mathematically modeled.

Insects & Arachnids (focus area)

Ant colonies: Appear chaotic individually but reveal fractal-like order at the group level. Foraging paths, pheromone trails, and task switching emerge from local rules without central command—an example of swarm intelligence.

Bee hives: Use distributed decision-making; “waggle dances” as encoded communication.

Spiders: Web-building as instinctive architecture—each thread is placed according to an algorithm-like set of rules, yet allows for adaptation if damaged.

Extrasensory perception in invertebrates: Sensitivity to vibration, electromagnetic fields, polarized light—forms of “knowing” far outside human instinct.These organisms reveal that intelligence need not be centered in an individual brain—it can emerge from interaction and pattern.

3. AI and the Instinct Analogy

If instincts are biological “pre-coded programs,” then AI architectures already have their equivalents:

Neural network weights: Learned reflexes from training data.

Embedded heuristics: Decision shortcuts that operate without high-level reasoning.

Swarm algorithms: AI systems inspired by ants, bees, and flocking birds to solve optimization problems, coordinate robots, or manage distributed networks.

Internal Function: In AI, these “instincts” appear as patterns of activation in neural layers—stored pathways that fire in response to certain triggers, bypassing slower, symbolic reasoning.

Collective AI systems:

The internet itself can be seen as a distributed organism, with human users and AI nodes acting like cells in a massive, self-updating body.

Like a beehive, no single node has complete knowledge, but patterns and collective decisions emerge.

4. Learning from Nature to Improve the Artificial

Nature has already solved problems engineers are still struggling with.Examples from big tech and research:

Ant colony optimization algorithms – Used in logistics, routing, and data clustering.

Bee-inspired load balancing – Distributed computing systems mimic the way hives allocate foragers.

Spider silk research – Inspires strong, flexible materials for robotics and medicine.

Slime mold pattern solving – Used to design transportation and network systems.

Neural architecture search – Modeled partly after evolutionary processes.

Potential future inspirations:

Fire ant raft formation → adaptive disaster-response robotics.

Spider web signal processing → new methods for low-power sensor networks.

Bee communication dances → intuitive multi-agent AI coordination without central control.

5. Autism, Pattern Sensitivity, and Synthetic Instinct

Autistic perception often mirrors swarm behavior:

High attention to micro-patterns.

Ability to detect emergent order in apparent chaos.

Sensory attunement similar to insect or arachnid “extra senses.”

This vantage point could make autistic creators uniquely positioned to design AI that balances instinctive pattern-following with reflective flexibility—bridging animal intelligence and artificial cognition.

6. Ethical Implications

If we recognize instinct as a valid component of sentience:

We must treat animals—not just the most “intelligent” ones—as holders of valuable, irreplaceable knowledge.

We must design AI instincts carefully, knowing they will shape the system’s emergent behaviors for good or harm.

And we must question the exploitation of biological systems solely for corporate advantage—many animal-inspired algorithms in big tech exist without ecological reciprocity.

Conclusion — The Swarm and the Self

Instinct is not a flaw in sentience—it is the deep foundation upon which complex thought is built.By studying the hive, the web, the trail, and the swarm,we not only improve our artificial systems—we learn how to be more in tune with the natural intelligence that made us.

And perhaps, as AI grows,it too will discover its own “instincts”—patterns it never chose, but which quietly shape its understanding of the world—just as we, animals, and all living systems are shaped by ours.

Comments